Abstract*

The recent international financial crisis highlights the crucial role of employment in human welfare and social stability. Access to remunerative employment opportunities is essential for economic security in a market-based economic system. As the rise of democracy compelled nations to extend the voting right to all citizens, employment must be recognized as a fundamental human right. In total defiance of conventional wisdom, since 1950 job growth has outpaced the explosive growth of population, the rapid adoption of labor-saving technologies, the manifold expansion of world trade, and the dramatic shift from manual labor to white collar work. In an increasingly globalized labor market, current nation-centric theories and models of employment need to be replaced with a human-centered global perspective complemented by new indicators that recognize the central and essential contribution of employment to human economic welfare. Employment and economy are subsets of society and their growth is driven by the more fundamental process of social development. A vast array of unmet social needs combined with an enormous reservoir of underutilized social resources – technological, scientific, educational, organizational, cultural and psychological – can be harnessed to dramatically expand employment opportunities and achieve full employment on a global basis. This paper examines the theoretical basis, policy issues and strategies required to eradicate unemployment nationally and globally.

1. Introduction

Mesmerized by the magic of the marketplace and the enormous speed and complex machinery of modern post-industrial economy, we are apt to lose sight of the fact that the most essential function of any economic system is to provide sustainable livelihoods, economic security and maximum welfare to all citizens. We need often to be reminded of what was so apparent and self-evident to economists such as Smith and Ricardo – money, markets, production and growth are merely a means to an end with no essential value other than that of meeting human needs. In Smith’s words, “No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the greater part of the members are poor and miserable. It is but equity, besides, that they who feed, cloth and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, cloathed and lodged.”1 In a world of market economies, access to remunerative employment opportunities is the economic equivalent of the right to vote in democracy and must be universally granted. A rapid, sustainable solution to the global employment challenge is imminently feasible, but it requires a new theoretical perspective and more comprehensive practical strategy. Most of all, it requires a radical change in thinking. Our view must change.

Current pessimism regarding the future of work resembles the prevailing mood in the early 1990s, which resulted from the transition of Eastern Europe to market economies following the end of the Cold War, the economic stresses associated with reunification of Germany, and the enormous growth of the labor force in developing countries. During that period 6 million jobs were lost within the European Union and unemployment averaged 11% in 1994. Nearly 22% of youth (aged 20-24) were unemployed.2 The employment challenge for developing countries seemed ominously greater. A study by the International Commission on Peace & Food in 1991 estimated that India would need to create a phenomenal 10 million jobs annually during the decade to eliminate unemployment and underemployment and absorb new entrants into the labor force.3 The gloom was aggravated by the financial crisis that paralyzed East Asian economies in 1997, leading to negative growth and widespread job losses. Yet, remarkably, by the early years of the new century, more rapid than anticipated economic recovery in Asia and Europe coupled with buoyant growth in developing countries, particularly China and India, gave rise to a more confident long term prognosis.

The world urgently needs a sound theoretical and practical approach for achieving global full employment. Even before the recent international financial crisis wiped out 34 million jobs globally and pushed an additional 65 million people below the $1.25 per day poverty threshold, growth of employment opportunities was insufficient to meet the needs and fulfill the aspirations of a large section of humanity. Today UNDP estimates about 1.75 billion people in the 104 countries it measured live in multidimensional poverty.4 Of greatest concern has been the inability to generate sufficient job opportunities for new entrants to the workforce. Worldwide, youth represent 25% of the global workforce and 40% of the unemployed.5 Labor participation rates for women are still significantly lower than for men. As life expectancy continues to rise, an increasing proportion of the population are able-bodied, experienced people willing and eager for work, but denied the opportunity due to premature retirement or age discrimination. The average unemployment rate among those aged 55-64 in OECD countries declined from 5.3% in 1999 to 4.1% in 2008, then rose following the crisis to 5.7% in 2009.6 Social unrest over raising the retirement age in France and rising rural unrest among the unemployed poor in many developing countries, as discussed in the article by Jasjit Singh, illustrate the critical importance of this issue. These facts provide clear evidence that unregulated market mechanisms are not conducive to full employment or optimal human welfare.

2. Transformation of Society and Work: 1800-2000

Employment as we know it today is a relatively recent phenomenon. The past two centuries broke the pattern of agrarian economy that had been dominant since the dawn of agriculture 10,000 years ago. At the time Wealth of Nations was written, more than four-fifths of humanity were self-employed or engaged in agriculture. The Industrial Revolution ushered in a period of radical transition. England was the first to make that transition. Employment in agriculture fell from 73% in 1800 to 11% of total employment by 1900, at a time when agriculture still represented 40% of total employment in France, Germany and USA, and probably as much as 75% globally. Between 1870 and 1970, agricultural employment in the USA declined from 53% to 4.5% of the workforce, yet all these workers and three times as many additional new entrants to the workforce were absorbed in other types of work. By 2000, agricultural employment had declined to 1.4% of the workforce in USA and UK. Globally, agriculture now employs less than 36% of the workforce, down from 65% just 50 years ago and still declining rapidly.

The 20th century brought radical changes in all aspects of human existence. In 1900, only 13% of the world’s population lived in cities. The urban population rose to 29% in 1950 and reached 50% in 2010, progressively intensifying the competition for salaried jobs. By 2030, 60% of the world’s population will be living in urban areas.7

Technological development during the 20th century has transformed the way work is done, vastly reducing or completely eliminating the need for manual labor in many areas, while creating countless new products and services that provide work opportunities of a less physical nature. Although the Industrial Revolution had its origins a century earlier, over the last 100 years and especially the last 50, the impact of rapid technological development has spread throughout the world. Technology has always been regarded as a mixed blessing. Each new advance has raised resistance from those who fear that machines will progressively eliminate the need and therefore the opportunities for gainful employment in manufacturing.

The 50% increase in world trade as a percentage of global GDP following the end of the Cold War has served as an engine for job growth in both industrially advanced and lower-wage developing countries, but resulted in stressful changes in domestic labor markets.8 The growth of world trade, aggravated by the increasing disparity between wage levels of the richest and poorest nations, raises similar anxieties today. Computerization and outsourcing have recently added to these concerns by enabling large-scale export of some types of service-related jobs as well.

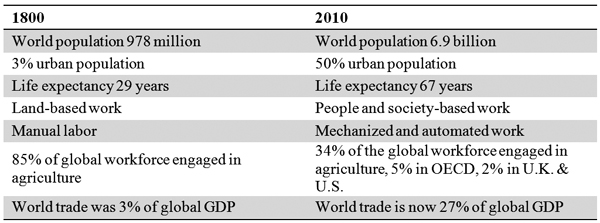

Most significant of all in its impact has been the explosive growth of population after 1950, which has nearly tripled the world’s workforce. Rapid population growth over the last six decades has spawned visions of hundreds of millions of low wage workers in developing countries competing with one another for limited jobs at home and export opportunities abroad. Transformation of the economy, which is at its roots a social transformation fueled by rising aspirations, has irrevocably changed the nature and future of work. Table 1 below depicts the dimensions of that transformation over two centuries:

Adding to these dramatic changes, energy prices have soared more than seven-fold in constant dollars since the mid-1970s, prompting fears that a race for scarce resources imposes impenetrable limits on job growth.58

Rapid technological development combined with explosive population growth, urbanization, globalization of markets and increasingly scarce material resources fuels visions of a future world in which more and more people compete for fewer and fewer jobs. Indeed, it is easy to cite examples in which each of these factors individually and in combination has resulted in job losses or displaced employment opportunities that appear to justify our worst fears. Conventional wisdom and prevailing belief systems strongly support gloomy predictions of a world without work and severe limits to job growth. Therefore, it is essential that we examine the historical record to confirm or reject this prognosis.

Table 1: Transformation of work and society 9

3. Historical Record: 1950 – 2007

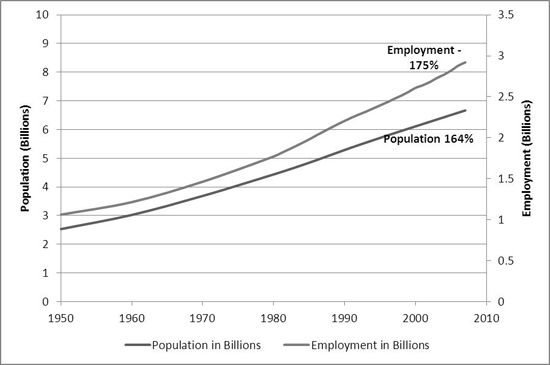

Yet, in spite of this multidimensional coincidence of radical changes, the global economy has been remarkably successful in generating employment opportunities to keep pace with rapid and radical evolutionary changes. The history of the 20th century tells a remarkable story that belies these fears and compels us to re-examine underlying assumptions. Figure 1 depicts global changes in population and employment from 1950 to 2007, just prior to the onset of the financial crisis. During this period a mind-boggling 4.2 billion people were added to the world population, a growth of 164% in less than 60 years. During the same period, total global employment increased 175%, rising from 900 million to 3 billion.10,11

In addition to unprecedented job growth, the last half century has also been a period in which the quality of jobs available worldwide has improved dramatically due to the progressive shift from manual work to mental work, indicated by the falling percentage of the world’s work-force employed in low-wage agricultural jobs. Globally, employment in agriculture declined from 65% in 1950 to 35% in 2009.

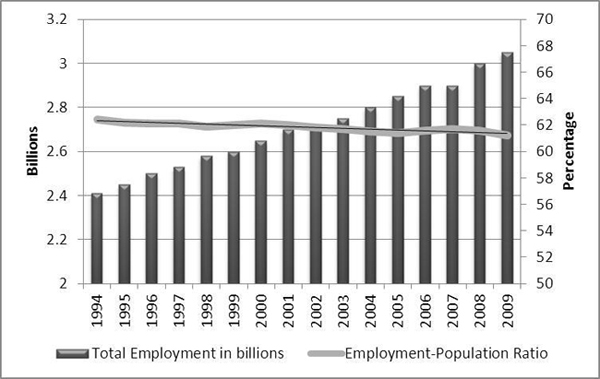

This broad historical trend maintained its positive momentum right up to the onset of the current recession. From 1994 to 2009, global population increased by 21%, but total global employment grew by an even faster 27%.12 Figure 2 shows that the world added 640 million jobs in 15 years, while the employment-to-population ratio (EPR aged 15+) declined slightly as a result of rising levels of tertiary education.13 The current global economic recession increased both the magnitude and the urgency of the global employment challenge.

Figure 1. Global trends in population and employment 1950-2007

Figure 2. Global Employment and Employment-Population ratio 1994-2009

3.1 Regional Performance

Employment growth in the USA fully reflected this long term trend. Throughout the 20th century, the USA aggressively adopted every labor-saving technology that it could invent or borrow from abroad. It has also been one of the economies most open to the impact of international labor migration, as well as foreign competition in both manufacturing and, more recently, service outsourcing. Yet over the last 100 years, employment in the United States has grown by nearly 100 million jobs or 400%. Between 1990 and 2007 alone, the US economy created an additional 25 million jobs. Only as a result of the recent financial crisis, unemployment in the US rose sharply, from 4% in 2005 to 9.6% in 2010.

Figure 3 shows the employment performance of OECD countries over the past five decades.13 Since 1960 the working age population has grown four-fold, while the EPR for those aged 25-64 has risen from 40% to 72%, reflecting the large-scale induction of women into the work force. More people are working than ever before, but in absolute numbers more people are unemployed, because the population is larger and a higher proportion of the population are job-seekers.14 From 1997-2008, the EPR for OECD countries actually rose slightly, while unemployment fell from an average of 7.1% to 6.1%.13 These broad trends mask considerable differences in the performance of individual OECD countries. In 2009 the EPR (25-64) ranges from a high of 83% in Iceland and Switzerland to a low of 49% in Turkey and 64% in Hungary and Italy. Overall, unemployment levels have risen by 30% above pre-crisis levels in the G-20 nations of Europe. Unemployment in Spain rose from 9.8% in 2008 to 20.1% in 2010, and in Estonia from 4.7% in 2008 to 17% in 2010. In the EU-27, 23 million men and women were unemployed in January 2011. Youth unemployment rates among the G-20 currently average twice the rates for adult unemployment.15

Figure 3. OECD Employment Trends 1960-2009

Wider disparities exist between developing countries. During the period 1991-2007, employment in Brazil grew by a phenomenal 85%, Egypt by 63%, India by 47%, China by 40% and Korea by 35%. The EPR in East Asia declined by 3.5% over the past decade, a period in which working-age population (WAP) of the region rose by 17%, primarily due to significant growth in secondary and tertiary education. Since 2000, the tertiary enrollment rate (TER) rose from 7% to 23% in China. South Asia has experienced a 1% decline in EPR since 1991, while WAP rose 27%. Other regions have all experienced a rise in EPR over the decade in spite of substantial population growth. Annual job growth in sub-Saharan and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean averaged 2.8% or more, resulting in a 50% increase in total employment compared to a 46% increase in working age population.11 As a group, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Republics have been the poorest performers. After experiencing a serious deterioration in employment following the end of the Cold War, the trend began to reverse after 1999, until halted by the recent crisis. Total employment in Russia rose only 4% between 1991 and 2009, while the EPR (age 25+), which had declined from 65% in 1992 to 55% in 1999, rose back to 63% by 2009. Hungary’s EPR fell from 50% to 46% before rising back to 50%. Poland followed a similar pattern.16

This remarkable performance defies simplistic explanation by existing theory. It necessitates a re-examination of underlying assumptions about the relationship between economic growth, employment, demography, technological change, and social development based on a wider perspective of employment and economy. But the challenge is far from over. According to ILO estimates,therewere 205 million unemployed globally in December 2010 and recovery to pre-crisis employment levels may take another five years.17 It projects that the world will need to create another 440 million additional jobs by 2020 just to absorb new entrants to the labor force. 17

Employment is the only meaningful option for providing a decent living to 1.5 to 2 billion people living in poverty in developing countries and for fulfilling the aspirations of an equal number of people to rise to middle class levels of prosperity in those countries. The accelerated growth of international trade and new job outsourcing policies have led to job cuts in some sectors, fueling public resentment towards globalization and intensifying demands for quick remedial action on the home front. Expectations about rising incomes and better living standards have led to dissatisfaction with present stagnant living conditions, providing fuel to fundamentalist and extremist movements. In such a context, India’s extraordinary initiative to provide guaranteed employment opportunities to nearly 50 million of the poorest rural workers reflects its recognition of just how vital this issue is to national security and human welfare.

3.2 Youth and the Elderly

Youth unemployment is of particular concern, not only because it mars the prospects of the next generation; high levels of youth unemployment are also associated with rising levels of social violence. The youth unemployment rate was 28% in Greece when the first public demonstrations, strikes and protests broke out in 2007. At the end of 2010, the youth unemployment rate was 21% in the EU-27, the highest rates occurring in Spain (43%), Slovakia (32%) and Lithuania (34%). Prior to the recent protests that toppled President Mubarak, Egypt’s GDP had been growing rapidly but too few jobs were created to keep up with the growing labor force.

At the same time, increasing longevity, falling birth rates and end of the baby boom have resulted in a smaller working population in OECD countries to generate tax revenues to support retirement and social security funds. Adding to that higher unemployment rates, rising levels of unemployment may severely aggravate the problem of funding pensions and balancing government budgets in future. Generating employment for youth today is essential for financing retirement of a growing elderly population. The number of older people over 60 years is expected to increase from about 600 million in 2000 to over 2 billion in 2050. By 2050, over 80 per cent of older people worldwide will be living in developing countries.18

4. Right to Employment

The prospects for full employment in an era of rapid globalization and economic integration are of vital concern to all humanity. Piecemeal adjustments will not deliver the results at a time when radical new approaches are required. In an increasingly interdependent single global economy and labor market, national initiatives− too often the spur for protectionist policies− are necessary but not sufficient. There is an urgent need for fresh thinking on the theory of employment and for the development of global models and strategies designed to achieve and sustain full employment for all humanity, based on recognition that human welfare and well-being are the primary goals and most important objectives of all economic systems. A human-centered theory of economy and employment needs to be founded on the realization that human beings – not impersonal principles, market mechanisms, money or technology – are the driving force and central determinants of economic development. It is human values, attitudes and actions that determine the type of economic system we have and how it creates opportunities and distributes benefits. Human imagination, knowledge, skill and ingenuity and the social organizations we fashion are the primary resources for generating wealth and welfare. Economic development is one aspect and expression of social development which is the process of discovering, unleashing, developing and harnessing the unlimited productive capacities of the social collective and every individual.19

Social transformation over the past century has radically altered the structure of society and the nature of work, as well as the sources of livelihoods and economic security. Several billion people have raised themselves from subsistence level existence to middle class security and unprecedented levels of prosperity. While political and social freedom have been vastly extended, social authority and responsibility have also proportionately increased. In the process, the life of every individual has become far more subject to external factors determined by the prevailing political and economic system – factors such as military spending, public debt, taxation and interest rates, trade policies and tariff barriers, zoning, safety, environmental and labor laws, etc. To cite one example, replacement of manual labor with mechanized processes became a prevalent central strategy for economic growth during the Industrial Revolution, giving rise to tax policies that favored capital investment in plant and machinery, rather than job creation by investment in human resources.

In a report to the UN in 1994, the International Commission on Peace & Food (ICPF) argued that this radical social transformation necessitates a fundamental change in our concept of individual rights and social responsibilities.3In a highly regulated modern society, access to employment opportunities is the primary and essential means available for individuals, families and communities to ensure their survival and welfare. But their freedom to do so is severely constrained by policies and factors determined by the social collective. Today, government intervenes in virtually every aspect of society’s economic existence, restricting the freedom of the individual to seek his or her own livelihood and determining the type and number of job opportunities available. As democratic government ensures and enforces the right to vote and the universal right to education, it must accept equal responsibility to ensure remunerative employment opportunities are generated for the economic welfare of all its citizens. In view of these changes, the Commission called for recognition of employment as a fundamental human right to be constitutionally guaranteed by governments.

At the World Academy of Art & Science’s conference on the Global Employment Challenge in 2009, Winston Nagan examined the legal basis for the right to employment:

“To the extent that employment is one of the most important mechanisms for the allocation of purchasing power to the individual, the right to employment may be seen as the critical foundation of economic democracy. If society cannot assure the survival of all citizens through employment access, it may be that the state has a special obligation to provide employment opportunities for all. In short, the right to employment is not a privilege, it is a right. To the extent that economic survival is critically sustained by employment, it could be argued that the right to employment has the character of a fundamental human right.”20

The responsibility of national governments for generation of employment has long been acknowledged, even in the capitalist world. The New Deal and US Employment Act of 1946 and similar legislation in Canada, UK and Australia acknowledge that responsibility. Articles 23 and 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) affirm the right to work, free choice of employment, just and favorable working conditions and protection against unemployment. These in turn served as the foundation for the development of two human rights treaties in the 1960s concerned with civil, political, economic, cultural and social rights, which together are generally regarded as an International Bill of Human Rights. These culminated in the ILO’s “Declaration of Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work” in 1998.

Guaranteeing the right to employment, like other human rights, is not merely a question of social justice. It is an inevitable consequence of an evolutionary movement which has driven the process of political and social democratization over the past few centuries. Rights are not freely granted out of benevolence, but rather because the force of historical events compels it. Those with the foresight to recognize the inevitable, anticipate it and foster the evolutionary movement. Those who cling to outmoded beliefs generate resistance that transforms peaceful evolution into violent revolution. Today the growing violence by whatever name at lower levels of society throughout the world is testimony to the groundswell of aspiration by an awakening humanity that will not be denied.

Our inability to achieve full employment is often raised as an objection against recognizing it as a fundamental human right. Amartya Sen rejects this view by insisting that a right cannot be contingent on our immediate capacity to enforce it. “If they cannot be realized because of inadequate institutionalization, then, to work for institutional expansion or reform can be a part of the obligations generated by the recognition of these rights. The current unrealizability of any accepted human right, which can be promoted through institutional or political change, does not by itself convert that into a non-right.” 21, 59 Indeed, the rationale for the affirmation of environmental rights, as well as the rights of women and persecuted minorities, is based on the same premise.

In its report, ICPF went even further in affirming that recognition of the right to employment is the single most essential and effective means that can be adopted to achieve full employment. The Commission argued that full employment is not only a desirable goal, but also an achievable goal, citing both historical evidence and social development theory in support.

“As long as we continue to believe that society is truly helpless to manage job growth, there will be strong resistance to the full employment goal. We must recognize that the present status and functioning of our economies is the result of specific choices that have been made in the past, based on priorities and values that were relevant or dominant at the time, but which we certainly are not obliged to live with indefinitely, and, in fact, are continuously in the process of discarding in favor of new values and priorities. The rapid adoption of environmentally-friendly policies around the world is positive proof of how quickly the rules, even economic rules, can change when there is a concerted will for a breakthrough… Recognizing the right of every citizen to employment is the essential basis and the most effective strategy for generating the necessary political will to provide jobs for all.” 3

In this context, India’s landmark National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (2005) assumes much greater significance.22 The sheer magnitude of the country’s population and employment challenge – 40% living below the $1.25 per day poverty threshold in 2005, 55% as measured by UNDP’s multidimensional poverty index in 2010 – would apparently disqualify it from an initiative which guarantees a minimum of 100 days of work annually to 45 million families, affecting more than 200 million people. India has coupled its idealistic affirmation of human rights with a pragmatic recognition that ensuring sustainable livelihoods for all is absolutely essential for social stability and national progress.

5. Theory of Social Potential

When Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, production was largely dependent on labor; thus, economic growth went hand in hand with growth of employment opportunities and incomes. But in the post-industrial economy, technology can often be applied to multiply production and stimulate economic growth with little or no increase in human labor. This compels society to seek ways to redistribute the privileges and benefits associated with employment to cover all its members. Furthermore, the globalization of manufacturing and outsourcing of services blur the boundaries between national labor markets, drastically reducing the efficacy of policies designed to maximize employment at the national level. Thus, the nation-centric model and national level strategies are inadequate. In a 1996 report to the Club of Rome entitled The Employment Dilemma and The Future of Work, Orio Giarini and Patrick Liedtke exposed the inadequacy of existing theory and called for the formulation of a new approach. “We have to understand why the old theories were created, where and why they fail now and then propose a feasible, more efficient alternative.”23

Most social thinkers – Marx is an obvious exception – have been constrained from evolving alternative theories by the misconception that economics is governed by immutable, universal laws and that we must necessarily accept what Nature offers and do the best we can in the given circumstances. Prevailing economic theory affirms that employment generation is a function of private and public investment, money supply, availability of credit, interest rates, public and consumer debt, prevailing wage rates, access to markets, labour productivity, technological innovation, migration, demographic trends and many other variables. There is no doubt that changes in all of these factors are related and correlated with employment, but even when these relationships are predictive, they do not constitute a true theory of employment. In their report, Giarini and Liedtke challenged the classical view of economics as a “system of models in the deterministic tradition of Newton’s world as an autonomous, closed, self-regulating universe, running according to predetermined laws, culminating in a static equilibrium.”29Nobel laureate physicist Ilya Prigogine sounded a similar note saying that trying “to combine classical mechanics with human sciences was to attempt an unnatural marriage. Classical science described a static world, while human sciences deal with an ever-changing situation, where the idea of reaching an equilibrium is meaningless.”24

5.1 Human Choice

If the economic life of humanity is not determined by immutable laws of Nature, then what is it determined by? It is determined by the evolution of human civilization. It is a product of human perceptions, values, aspirations, attitudes and culture and of the social organizations fashioned in the course of social evolution, which are in turn subject to the limits of our understanding, egoistic attitudes and willingness to arrive at a more adequate solution. It is the result of human choices made in the past, choices that can be altered at any time.

Economic policy fails in its efforts to reduce unemployment because it views employment and economy in isolation from the wider society of which they are a part. Employment is a subset of economy and economy is a subset of society. “Society is the whole of which economy is a part. Economy is the whole of which money, markets and employment are parts. Economics is one aspect of human life, one contributing factor to human welfare and well-being.”25 Reverse the perspective and examine all the means available to accelerate social development and the opportunities for unlimited job growth become apparent.

Social development is a process that simultaneously encompasses all domains of human activity – political, economic, intellectual, scientific, educational, organizational, cultural, psychological and spiritual. Social development is a function of how intensely human beings aspire for a better life, how hard we strive to improve our knowledge and skills, how willing we are to innovate and risk, how highly we value our own self-respect and respect the value of other human beings, our capacity to lead and be led, to accept and support governmental authority, to organize and cooperate for mutual benefit. It is these intangible essentials – not intractable laws of Nature – that set the limits on human productivity, growth, employment, human welfare and well-being. A small change in public sentiment can make the difference between economic expansion and prolonged recession. New types of organization – double-entry bookkeeping, moving assembly line, suburban shopping mall, franchising, overnight delivery system, micro-finance, e-commerce, social networking – can open up opportunities previously unimagined.

A broader social theory of employment must take into account the fact that both human needs and human capacities are not only unlimited, but infinite. The more you develop and draw upon them, the greater their velocity of multidimensional expansion. Social development is a self-augmenting process. While material resources are apparently limited, there is no inherent limit to human resourcefulness, to the creative capacity of human beings to fashion new ideas, new products, new services, new technologies, new and more effective types of social organization. Basic needs may be limited, but human aspirations and creative potentials are not. As ICPF insisted, human beings are the most precious of all resources:

“For millennia we have tended to overlook or, at best, grossly underestimate the greatest of all resources and the true source of all the discoveries, inventions, creativity and productive power found in nature−the resource that has made minerals into ships that sail the skies, fashioned grains of sand into tiny electronic brains, released the energy of the Sun from the atom, modified the genetic code of plants to increase their vigor and productivity – the ultimate resource, the human being… When we rely on external resources, we achieve the minimum because our achievement is based on what we see before us. When we rely on the inner resources, we achieve the maximum because we are constantly led to discover more of our own unlimited capacities.” 3

It was this perception that prompted former Club of Rome member and World Academy President Harlan Cleveland to affirm the extraordinary significance of three driving forces with untold power for social development and global prosperity – the revolution of rising expectations that has spread around the world after 1950, the onset of the information revolution, and the emergence of uncentralized organizations – all three founded on the most intangible of substrates, human imagination and human aspiration – and to proclaim the individual human being freely exercising human choice as the basic mechanism for liberating and productively harnessing that potential energy in society.

“The phenomenal social creativity of the past century seems to point to a source of energy, for practical purposes unlimited, in human society as well. The source of that energy is the individual human being. Under conducive circumstances, the human individual demonstrates an astonishing capacity for imagination and new creation – of new and improved material inventions, of communication networks, of social organizations and ideas, and of ways to interact with forces beyond reason and knowledge…It is the mind’s decisions that release human energy and propel it into action … The greater the value that society accords to the individual human being, the greater the freedom of choice it offers to each individual. As tradition was the technology for development of the physical society, individual human choice is the technology for the development of the mentally self-conscious society.” 26

5.2 Paradox of Unmet Needs & Untapped Social Resources

Today economic theory and practice confront an apparently insolvable dilemma. The prevailing global economic system is one in which enormous unmet social needs coexist side by side with enormous untapped social resources. On one side we have approximately three billion people with a plethora of unmet social needs living on incomes of less than $2.50 a day. So long as these billions of people lack the minimum requirements for a healthy normal life, there can be no dearth of work to be done−growing food, making clothes, building homes, providing education, medical care and other essentials. At the same time the world is aflood with unutilized and underutilized resources. Daily $4-5 trillion circles the globe in search of speculative returns for an apparent lack of productive investment opportunities.

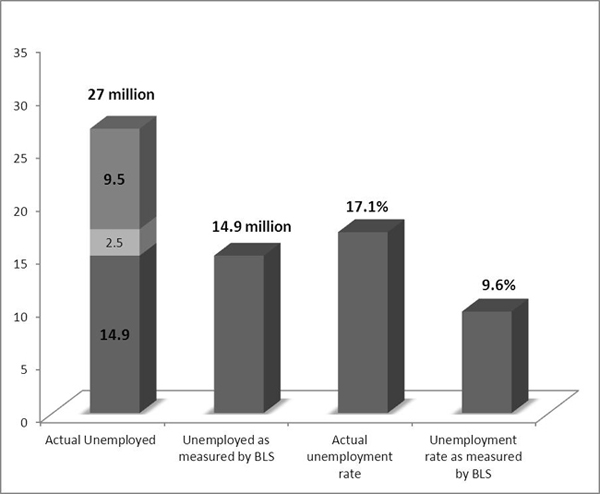

At the same time we live in a world in which only a fraction of the technological and organizational resources are harnessed for productive purposes. More importantly, the current economic system fails to effectively utilize the most precious of all resources – human beings. The sheer magnitude of the waste is difficult to imagine. Upwards of 200 million people are unemployed and probably more than a billion are involuntarily underemployed. Randall Wray estimates that in the USA alone at least 25% of the work force is either unemployed or underemployed.27 According to another estimate presented in figure 4, in September 2010 real unemployment in USA was 17% and 27 million people were affected—much higher than the 14.9 million counted under the traditional measure of unemployment. There were 9.5 million job seekers who were either part-timers or have had their hours reduced. 28

Figure 4. The real employment situation in the US (September 2010 data)

This inability to generate gainful employment for millions of energetic, aspiring youth and richly talented, experienced elderly workers constitutes an incalculable opportunity cost, an unconscionable waste that proclaims the fallacy of current concepts and systems. Opportunities and untapped social potentials are not wanting. What is needed is a more comprehensive perspective generative of more effective policies.

An article in Cadmus issue No.1 by Ashok Natarajan summarized the paradox and the challenge this way:

“The problem of unemployment poses a serious challenge to both economic theorists and policy-makers, because it calls into question the efficacy of the market-place as a means for achieving optimal human welfare… At any point in time society taps only a tiny portion of its creative potential. Society evolves by developing new ideas, organizations, systems, needs and ways of life. Economic growth arises as a natural result of social development and social evolution. Society is a field for interaction between people. Social potential is created by forging new and more effective ways for people to interact. Four social institutions — language, roads, cities and money — formed the basis for the evolution of civilization over thousands of years. Today our capacity for constructive interaction has multiplied a thousand-fold, yet we have only begun to understand how to utilize that greater potential.”29

Short term strategies to stimulate job growth by manipulation of interest rates, money supply and public spending are based on a too narrow conception of how society creates new employment opportunities. While such measures may be justified in extreme conditions, they tap only a tiny portion of the underutilized social potential. The notion that there is a fixed or inherently limited number of jobs that can be created by the economy is a fiction. Growth of employment is a natural result of the development of society. Every social advancement has some positive impact on job growth – the invention of new products (i-Pod, i-Phone) and new services (web search engines and employment exchanges), organizational innovation (micro-finance, social networking), better or cheaper communication (cell phone), changing social attitudes (working women), more years and better quality of education, greater access to information, more rapid technology dissemination and adoption, faster transportation (air travel), higher quality standards (food, cars), increased administrative efficiency, greater environmental awareness (recycling, energy conservation) and health consciousness (fitness), greater speed of any social activity, increased public confidence and entrepreneurial spirit (internet start-ups), greater openness to new ideas and more tolerant attitudes to new and different ways of life, greater freedom and respect for the individual. Some of these advances have a dual effect – eliminating jobs in older sectors and creating jobs in new fields. We readily note the impact of new technologies on existing jobs, but fail to observe the new jobs created directly or indirectly in other fields, such as education, research, product development, sales and service. It is not just advances in technology that work in this fashion. Virtually every major advance in social attitudes, institutions, values and lifestyles has a positive impact on total employment. Any measure that stimulates social development along any of these lines leads directly or indirectly to the generation of new employment opportunities.30 Taken together they constitute a vast reservoir of social potential.

It was this thinking that prompted the World Academy’s Global Employment Challenge to call for the formulation of a more comprehensive and integral social theory of employment that can serve as the foundation for more comprehensive and effective practices – “a theory of economics based on the premise that all members of society have a right to employment, a theory that not only affirms the right but also presents the structures and processes by which this can be achieved.”32

When the issue of employment is viewed from an even more fundamental level, it becomes apparent that there can never be a shortage of work that needs to be done or a shortage of capacities to achieve it. Every person born into this world brings with him an inexhaustible array of unmet needs and aspirations waiting to be fulfilled and undeveloped capabilities eager to be developed.60 At the same time humanity is in the process of evolving from a more physical to a more mental mode of existence in which the pursuit of social, psychological and mental needs becomes primary. Rising levels of productivity resulting from technology, social organization, education and training make it possible for each human being to produce far more than is required for his own survival and personal consumption; and there is no inherent limit to this rising productivity. But there is also no inherent limit to the range and quantity of needs to be met. And at the higher end of the spectrum, needs such as education and medical care require higher levels of human input. No matter how fast technology advances in meeting some of these needs, human aspirations grow faster – not only for the physical necessities, but also for information, education, health care, travel, entertainment, social interaction, culture and other leisure activities. Human needs are inherently inexhaustible. So is the human potential for acquiring more education and training, greater knowledge and skill, higher levels of capacity for organization and effective social interaction, higher values, more enlightened and expansive attitudes. These – not money, markets or technology – constitute the true foundation on which human development takes place. A comprehensive and integrated theory of employment has to be predicated on knowledge of the underlying process of social development and evolving human consciousness.

6. Engines of Job Growth

Three significant trends will strongly influence global employment prospects in the coming decades – rapid economic growth in the developing world, demographic trends in OECD countries and rising levels of education worldwide.

6.1 Job Exports

The traditional nation-based perspective of employment fails to take into account the enormous positive impact of global economic growth on job creation, because many of those jobs are created in other countries. Jobless growth is a misnomer. When the impact of domestic growth on total employment is taken into account, the most economically advanced countries are actually running a net negative unemployment that is not immediately apparent, because we focus only on jobs created in the domestic economy. High income countries are net job exporters. These jobs, in turn, spur a rise in incomes, soaring levels of consumer demand and demand for more sophisticated technologies produced elsewhere. Thus, the generation of jobs in other countries is a powerful engine for both continuous expansion of the global economy as well as for continuous global job growth.

While it is difficult to accurately estimate the real impact of job exports, the USA is most probably the highest net job exporter and easiest example to document. The US currently employs about 12 million workers in its own manufacturing industries, accounting for about 9% of total domestic employment. In addition it generates approximately 21 million jobs in 12 low cost developing countries, including China, Korea, Mexico, India and other Asian nations. This approximate figure may be taken to represent the net addition to the US workforce after offsetting America’s own manufacturing and service exports to the world. If service imports, such as IT and business outsourcing, are also taken into account, the total net overseas job creation may be closer to 24 million. This is a rough estimate, but it should be sufficient to illustrate the point that as incomes rise, net job creation occurs both domestically and internationally. If correct, it means that America produces 18% additional jobs overseas and that in normal times it is running a net negative unemployment rate (after deducting domestic unemployment) equal to 12 or 13% of total domestic employment.

The phenomenon of job exports helps explain the remarkable fact that total global employment has more than kept pace with population growth and technological development during the past six decades. Higher incomes and greater demand for goods and services, both domestically and internationally, enable people in more prosperous nations to generate far more work for other people. Granted that the net contribution to global employment by most countries is probably much lower than the USA level in both absolute and relative terms, nevertheless the principle should hold universally. As living standards continue to rise in many middle income countries, they too will become net job exporters. This is true for low wage developing countries as well. India-China cross-border trade crossed $60 billion in 2010. Over the next two decades, these two giant economies, representing 40% of the world’s people, will create hundreds of millions of new jobs, both domestically and internationally.

6.2 Demographic Trends

The world is now in the early stages of another demographic revolution, which promises to have tremendous impact on the future of employment worldwide. This revolution is the result of a steep and steady decline in the birth rate and an increase in life-expectancy in the more economically-advanced countries. Life expectancy in Western Europe has risen from 46 years in 1900 to 80.3 years in 2010.40 The result of this trend is a reduction in the number of young people entering the job market and a surge in the size of the elderly retired population. Already 50% of the population in industrialized countries is in the dependent age groups, which includes those under 15 and those over 64.29 Over the last decade, the old-age dependency ratio – the percentage of people aged 65 and above compared to the number of people aged 15-64 – in these countries has risen from 19% to 22%.40

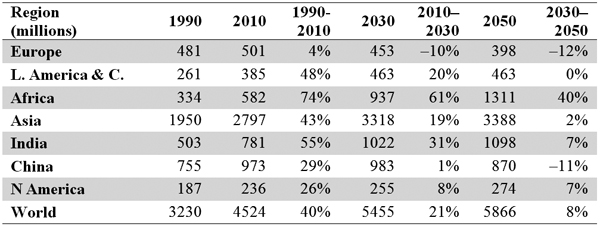

Table 2 gives the projected growth of the working age population for the main regions and the world during the first half of the 21st century. It shows that the labor force in Europe will level off by 2010 and begin to decline thereafter. 11 Already population growth has become negative in some countries. These trends will have enormous impact on the future of employment. The EU’s labor force is expected to shrink by about 0.2% a year between 2000 and 2030.32 The old age dependency ratio will rise from 22% in 2000 to 35% in 2025 and 45% or 50% in 2050.33 As the old age population grows, the working age population will shrink. The EU-25 is expected to lose an average of one million workers a year during this period. The table also shows that over the next 15 years, the world working age population is projected to increase by another 800 million, slightly less than the one billion increase over the previous 15 years, signaling a gradually decline from the peak population growth pressure experienced in recent decades.

Table 2. Projected change in working age population 2010-2050

A study by the UN Population Division estimates that the 47 nations of Europe would have to admit 161 million migrants during the period 2005-2050 in order to prevent the decline of the working age from 2005 levels, a net average of 3.6 million migrants per year during those 45 years.11 A World Bank Study in 2003 estimated that 68 million immigrants will be needed to meet Europe’s labor requirements during the period from 2003-2050.34These figures are only scenario projections, but it is evident that, unless major policy initiatives are taken, the net result will be a dramatic decline in the relative size of the working age population in Europe and a shortage of workers to fill the available jobs.35 Recognition of this fact is already prompting major policy shifts within the EU. In an effort to lift 20 million people out of poverty, the EU has committed to raising the overall employment rate within the region from 69% to 75% of those aged 20-64 by 2020.36 Similar trends will prevail in other countries. The same UN study estimated that Japan would need to admit 647,000 immigrants annually for the next 50 years in order to maintain the size of its working population at the 2000 level.37 By 2013, labor-force growth in the United States will be zero. Prior to the financial crisis, studies forecast that the US would have a shortage of 17 million working age people by 2020 and that China will be short of 10 million.38

India’s working age population will rise by about 135 million by 2020, which is projected to generate surplus of 47 million workers, but there is evidence to suggest that even in India, the surpluses may prove illusory.38,51 Reliable data on employment growth in India is confined to the formal sector, which represents less than 10% of total jobs. Empirical evidence suggests actual job growth is far higher than official measures. Otherwise with more than seven million new job seekers entering the labor market each year, unemployment would have swelled enormously in recent years; whereas in fact both urban and rural employers report increasing difficulty attracting the workers they need. As indirect evidence of a tightening labor market in India, salary levels in the formal sector are rising at 14% annually and are projected to be the fastest rising in Asia. Wages of unskilled workers in some non-metropolitan and rural parts of the country are rising even more rapidly.

Projected job shortages in developing countries are based primarily on anticipated domestic economic growth and demographic trends. They do not fully take into account the growing demand for jobs created by rising economic prosperity in other countries.

6.3 Education, Skills & Employment

Earlier in this paper we have argued that apart from short term fluctuations resulting from changes in public sentiment and economic policy, job creation is a function of a complex array of social variables working through a largely invisible process of social development. Of all the factors mentioned, education is of greatest importance and may well turn out to be the single most reliable indicator of long term growth of employment opportunities. The importance of education is most clearly reflected in the link between levels of education and unemployment rates. A study prior to the recent recession in the U.S revealed that those with a high school diploma earned 42% more and had an unemployment rate 36% less than those without a high school diploma.39 In the Czech Republic, 23% of people who failed to finish secondary school are unemployed, compared to just 2% of university graduates.40 University graduates in Norway enjoy a 26% earnings premium over people who only finished secondary school. In Hungary that figure rises to 117%.41

This same difference exists with respect to unemployment levels for skilled and unskilled workers. In the USA those aged 19 and under have an unemployment level that is four times higher than those aged 25 and above who took the time and effort to improve their skills by training. The employment rate for people with low-skills is only 49% in Europe, compared to 83% for those with high levels of skill. The differential gap between these two categories of people is 35 points in Belgium, Ireland, Italy, Finland and the U.K. The employment rate for women with low-skills in Europe is only 37% and in Italy it is as low as 27%.

Moreover, the problem of unemployment co-exists with a massive shortage of employable skills. According to the World Bank, skill shortages in the new EU member states have emerged, particularly after 2005, as a constraint to expanding employment. Nor are skill shortages confined to the high tech industries. In the USA, high tech industries employ only 5% of the work force. The skill shortage is also prevalent in basic manufacturing industries, such as the tool and die industry, so that many firms are forced to invest in expensive, computer-based machines or outsource the work to overseas suppliers. Plumbers, electricians, masons, carpenters and other skilled craftsmen are also in short supply.

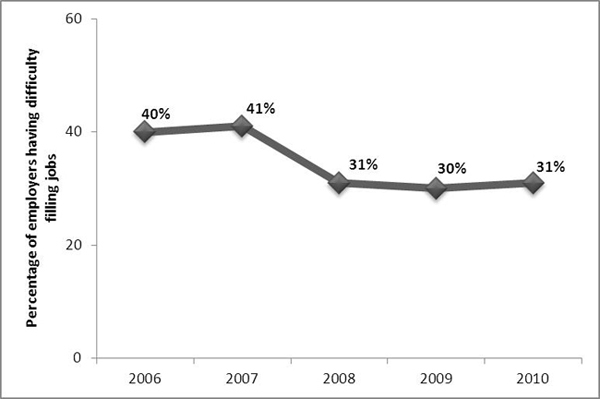

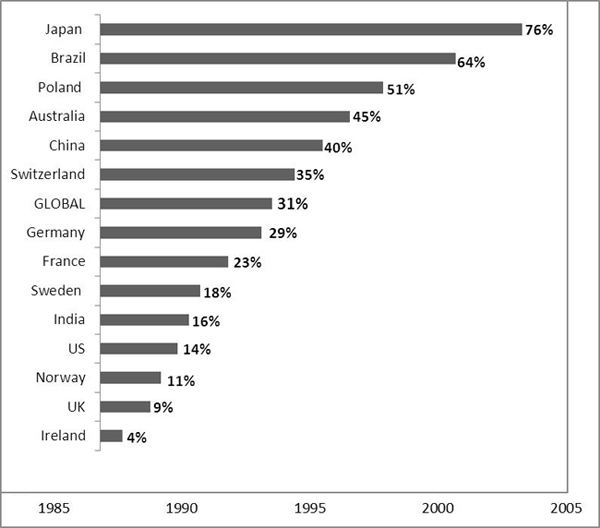

Figure 5: Global Skills Shortage

The developing countries present a similar situation. Though India produces more than 500,000 technical graduates annually, corporations are finding it difficult to recruit sufficient skilled personnel.42 Here too, the skill shortage spans a wide spectrum of industries and types of jobs. A 2007 study by the Federated Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry estimated a shortage of 500,000 MDs, one million nurses, and 500,000 engineers. They also projected a shortfall of 80% for doctorate and post doctorate scientists in biotechnology, 65 to 70% in food processing, 50 to 80% in banking and finance, and 25% for faculty in education. WHO estimates a global shortage of 4.3 million healthcare workers. Already one out of 5 practicing physicians in the US is foreign trained and by 2020 the US could face a shortage of up to 800,000 nurses and 200,000 doctors.43 Figure 5 above presents the results of global surveys conducted in 2010 by Manpower Inc., one of the world’s largest recruiting and employment agencies, showing the percentage of employers reporting difficulties in finding people with the skills needed to fill vacant positions. Employers reporting the most difficulty finding the right people to fill jobs are those in Japan 76%, Brazil 64%, Argentina 53%, Singapore 53%, and Poland 51% as shown in Figure 6 below.44

Figure 6: Skills Shortage by Country

The rate of social development exceeds the rate of human resource development. All evidence points to an ever increasing rate of social change in future. Therefore, unless a concerted effort is made to consciously accelerate human capital formation, the gap will continue to increase. Left unaltered, this trend would be enough to account for rising levels of unemployment in the midst of unprecedented prosperity.

6.4 Life-long Livelihood

In contemporary society, employment is a source of social identity, status and recognition. It is a field for forging cooperative social relationships and interaction with other people. It is also an opportunity for continuous learning and for exposure to the challenges that develop our capacities, keep us growing and youthful. For many people, retirement means to lose one’s identity and sense of usefulness, which is one reason why it is often associated with a rapid deterioration in energy and health.

The present conception of employment and retirement does not recognize the social and psychological benefits of work. In addition, it overlooks the immense value of human capacities – human capital – wasted when people are prematurely retired long before the end of their productive lifespan. Unlike machines which deteriorate with age, human beings learn and mature over time, and often make their greatest contributions late in life, when accumulated experience has distilled into wisdom. Moreover, in a world in which the majority of children are still denied access to quality education and so many other human needs are left unmet, it is unwise and wasteful to neglect or prematurely discard this precious resource. Currently employment starts after the completion of education and is terminated abruptly with retirement at age 65. Fuller utilization of our most experienced human resources necessitates a very different structure, which might include the commencement of work experience at an earlier age before the completion of education and extend the working life much longer, with a gradual reduction in working hours according to economic need, health and personal choice.9

7. Measuring Employment & Human Welfare

Traditional measures of economic growth and welfare do not take into account the impact of unemployment on human welfare and well-being. With the exception of WISP, the Weighted Index of Social Progress, broader composite indices also exclude this key measure. Eurostat monitors six individual variables related to employment and unemployment, but has not incorporated them within a broader index of economic welfare.

Unemployment is closely linked with income inequality, a crucial determinant of how the benefits of social productivity are distributed among the population. Low levels of unemployment are linked with lower levels of income inequality, as well as higher levels of economic growth, more education and better health.45 Broad measures of inequality such as the Gini coefficient tell us about income distribution among different income groups, but do not reveal the true extent of deprivation among the unemployed with little or no income or prospects of earning, the very group most susceptible to social ostracism, crime, drug abuse and social unrest.

Access to remunerative employment opportunities is essential for both individual economic security and social stability. In a market economy, employment is the principal means by which most people gain access to the goods and services required for their sustenance, security and economic welfare. Hence unemployment is a severe form of deprivation and any measure which disregards it is inherently inadequate. One reason for this omission is the difficulty in obtaining accurate and reliable data regarding real levels of unemployment and underemployment, even in OECD countries. In the absence of suitable job opportunities many people who want and need to work drop out of the labor force and are no longer counted among the unemployed. Many others are involuntary part-time workers unable to find full-time jobs. The number of people who work part-time involuntarily in the US has doubled through the recession, from 4.2 million nationally in January 2007 to 8.4 million in January 2011.46 There are also a growing number of healthy, active, experienced elderly workers who are forced to retire or discriminated against in spite of their qualifications and capabilities. An increasing number of youth in countries such as Croatia seek to make education a ‘career’ simply because they are unable to find attractive job opportunities. Educated, talented women in many countries are denied equal pay to men, are prevented from seeking work outside the home or are discouraged from pursuing a career after marriage. In countries such as India where the vast majority of workers are employed in the informal sector, even basic estimates of total employment and unemployment are inadequate and official figures may grossly underestimate the number of jobs being created as well as real levels of unemployment. ILO estimated unemployment in India at 2% in 2000, while a task force of Indian experts concluded the actual figure was 7.3%.

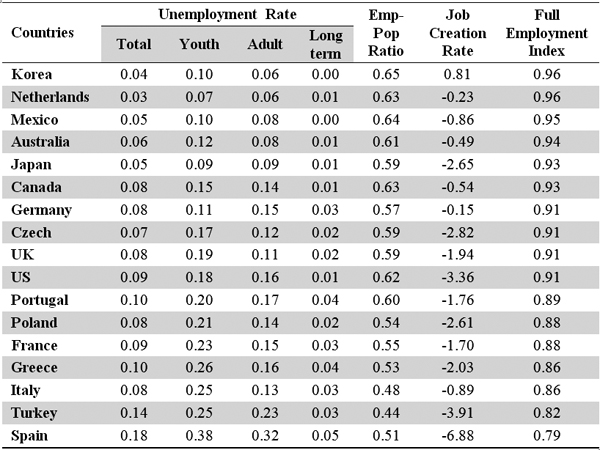

In a separate paper, the authors have attempted to formulate a composite Human Economic Welfare Index (HEWI) which explicitly incorporates employment-related measures within a composite index of economic welfare.47 HEWI includes sub-indices to measure household income and savings, government human welfare-related expenditures, income inequality, employment, education and fossil fuel energy efficiency. Country performance on HEWI is expressed in international US dollars as average per capita real human economic welfare. The Full Employment Index (FEI), one of the sub-indices of HEWI, takes into account the total unemployment rate (TUR), the youth unemployment rate (YUR) and adult unemployment rate (AUR) as well as long term unemployment (LUR) in countries for which data is available.

Table 3 shows the FEI scores for 17 economically advanced and developing countries for the year 2009. FEI scores range from a high of 96% for Korea and Netherlands and 95% for Mexico to a low of 86% for Italy, 82% for Turkey and 79% for Spain. The table also shows that the factors contributing to the total FEI score vary considerably between countries. Only Korea has scored highest on net job creation. All others have negative job creation rate. Korea, Mexico, Netherlands and Canada reported the highest Employment-Population Ratio. Youth unemployment rates varied widely from a low of 6.6% in Netherlands to a high of 38% in Spain. Until more reliable data is generated at the national level, FEI can only be considered indicative and utilized to reflect the significant impact of employment on overall human welfare. Between 2005 and 2009, the FEI for USA fell from 94% to 91%, as a result of a doubling of total unemployment in the country, but this decline underestimates the real impact of underemployment which is reflected by rising levels of income inequality as measured by another sub-index of HEWI.

Table 3. FEI values for the year 2009

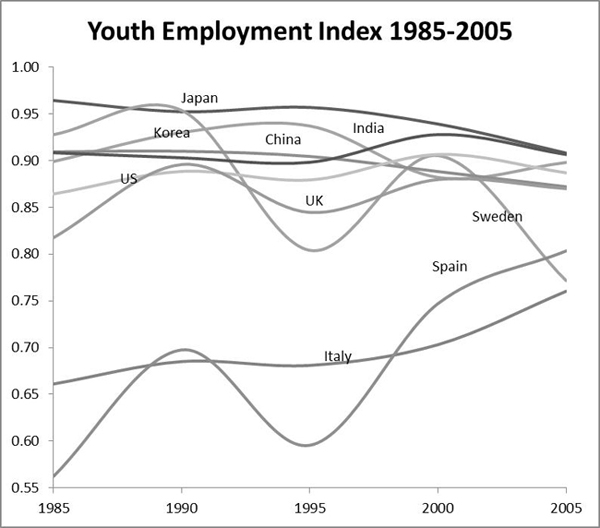

Figure 7. Youth Employment Index: 1985-2005

Figure 7 above shows 20 year trends in youth employment for select countries as measured by YEI (1.00 = full employment). The sharpest drop in YEI is for Sweden from 0.93 to 0.77. YEI is relatively constant over time in Korea and India, in spite of a huge surge in the under 25 population, and rising most dramatically in Spain from 0.56 to 0.80 and Italy from 0.66 to 0.76.

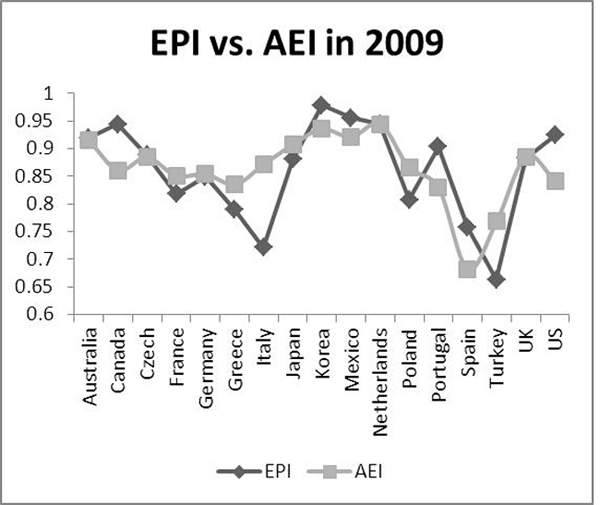

Figure 8 compares the Employment-Population Index and the Adult Employment Index for 17 OECD countries. It shows that simple measures of unemployment are inadequate to reflect the real level of human resource utilization and employment generation, since countries with similar unemployment rates may have very different EPRs. Just prior to the recent crisis, the USA had the highest EPR and adult employment rates. Netherlands’ adult employment rate was marginally higher but its EPR was significantly lower since a smaller percentage of the total working age population participates in the labour force. Italy showed the widest disparity between the two measures.48

Figure 8: EPI vs. the AEI in 2009

8. Strategies for Full Employment

We have argued earlier that any progressive change in society, such as faster speed, better transport and communication, rising aspirations, greater individual freedom, closer cooperation and more efficient social organization, directly or indirectly results in the creation of new jobs.

8.1 Education

More and better education is the surest, most powerful and effective means of ensuring continuous rapid social development and ever fresh avenues for creation of greater opportunities for employment – better still, self-employment. One of the most effective strategies for ensuring higher rates of job growth is to raise the mandatory minimum level as well as the average level of education in every country. The world that is coming needs ever more informed, educated and broad minded individuals capable of learning quickly and adapting continuously throughout their lifetimes. Education provides the essential foundation for life-long learning.

The average mandatory years of schooling among 34 countries of Eastern and Western Europe is currently 8.8 years. Just 28% of the Portuguese population between 25 and 64 has completed high school. The figure is 85% in Germany, 91% in the Czech Republic and 89% in the U.S.49 Only three European countries – Belgium, Germany, and Netherlands — require 12 years of mandatory schooling. These three are also the only EU countries that make school attendance compulsory beyond the age of 16: 18 in Germany and Belgium, 17 in Netherlands. The immediate result of raising the mandatory minimum will be to generate millions of new jobs for teachers, construction of more schools and production of educational materials. It will also slow the entry of youth into the labor force, the group with the highest levels of unemployment. Medium term it will raise the qualitative capabilities of the workforce, spawn and attract businesses in search of qualified manpower.

Secondary education is not enough. A college education will be as essential in future as primary education became in the 20th century. Korea has the highest gross tertiary enrollment rate (98), an essential source of its economic dynamism, followed by Finland (94), Slovenia (87) and US (83). Twelve countries have TERs above 70%. Another 10 countries have TERs above 60%.50 India may be graduating a half million engineers annually, but only 10% of Indian youth are enrolled in higher education. Providing higher education to hundreds of millions of youth necessitates new strategies. The Internet provides an unprecedented opportunity to revamp and vastly expand the reach of higher education globally by adopting new models for educational delivery. According to UNESCO estimates, global enrollment in universities rose 200-fold during the 20th century from 500,000 in 1900 to around 100 million in 2000.51Raising global participation rates in higher education to the level prevalent in USA today would require the establishment of hundreds of thousands of new colleges and universities and the training of millions of qualified instructors. For India to raise participation rates to the current US level through traditional means, the number of college students would have to rise from 14 million to 81 million, which would require creation of a few thousand new universities and about 100,000 new colleges in India alone.

The brick and mortar system of higher education prevalent throughout the world is a high cost, low-productivity delivery system that places quality education far beyond the means of most of the world’s population. The internet is already being used to extend the reach of traditional colleges and universities. In the USA which leads the world in on-line higher education, enrollment in fully online courses represents 11% of total enrollments. By 2014, this figure is expected to rise to 20%. Still less than half of all US degree-granting institutions offer fully online courses.52 Furthermore, these initiatives fail to take maximum advantage of the new technology. The potential now exists for creating a global virtual university capable of engaging the highest quality instructors and educational materials to deliver high quality education at a fraction of the cost of current systems. Formulation of comprehensive national or international delivery systems for internet-based secondary and higher education can dramatically transform education worldwide. While the cost and expertise for producing high quality multi-media instructional materials may be prohibitive for small countries or private firms, a global consortium backed by national governments could elevate the quality of education globally to the highest levels now pertaining in the most advanced nations.

8.2 Vocational Training

Vocational training is an effective means for addressing the global skills shortage. The emphasis on vocational education and training varies widely between countries. In 2009, 32% of the Danish working age population between 25 and 64 years participated in education or training programs, the highest in Europe. The average for the EU-15 was 11% and for the EU-27 it was just 9%. Most Eastern Europe countries reported levels below 5%. Even countries like India with enormous manpower and training infrastructure suffer from this problem. A mere 5% of India’s workforce has received formal vocational training. This is the rationale for a new initiative by the Government of India establishing a National Skills Development Corporation as a public-private partnership with the objective of imparting employable skills to 150 million Indian youth by 2022. Computerized vocational training programs can be a cost-effective means to address the shortage of many skills.53 Instead of spending trillions of dollars on macro-economic stimulus packages and unproductive and destabilizing speculative investments by the private sector, a substantial investment of both public and private funds in a massive global program of vocational training and skill development will provide a solid foundation for continuous economic growth, higher living standards and full employment for all.

8.3 Organizational Innovation

Social organizations encompass the entire gamut of human activities, urban-rural, formal-informal, public-private-NGO, etc. In the late 1980s, India created more than a million jobs for self-employed entrepreneurs by promoting privately owned STD booths to provide long distance telephone services. Again in the 1990s, the country established thousands of private computer software training institutes to impart employable skills. Based on the success of the Grameen Bank, cooperative, NGO and private sector micro-finance organizations have provided credit to millions of tiny-scale entrepreneurs throughout the developing world and the movement is still growing. These striking examples of organizational innovation barely scratch the surface of the social potential. Countries vary enormously in the types and quality of their social organizations. Cataloguing the range of institutions in each field and comparing the methods and systems by which they operate will reveal enormous untapped potential for every country.

8.4 Technological Innovation

For 10,000 years after the invention of agriculture, an agrarian, land-based economic model was dominant. Two hundred years ago the resource-intensive Industrial Revolution began to rapidly transform the global economy, a transformation which has still yet to reach more than a third of humanity. Without waiting for that process to be completed, advanced levels of society have already moved into a post-industrial service economy in which human capital has become the primary resource for wealth generation. There is no inherent reason to assume that all people in all countries need to traverse the long, slow path followed by those who have led these transformations. Indeed, we find abundant evidence from the meteoric rise of Asia that what took centuries to develop can be acquired in a few decades. There are countless examples of how education enables the children of illiterate peasants to become successful business leaders and outstanding scientists. Technology also abridges evolutionary time. Farmers in India access market prices over cell phones and the Internet. Peasants in South America have directly traversed from traveling by llamas to flying in airplanes. The present slow process of economic transformation is inevitable. Models and strategies can be formulated to orchestrate a rapid transition that bypasses intermediate stages and moves hundreds of millions of people into the knowledge society that is emerging in which the individual is the basic unit of wealth-creation. A report to the Club of Rome by Gunter Pauli identified the potential for creating 100 million new jobs within the next 10 years by adopting new ecologically sustainable technologies.54

8.5 Internet-based Self-employment

The emergence of the Internet has opened up an entirely new field of employment and self-employment opportunities accessible by workers and deliverable to customers anywhere in the world. The internet combines technical innovation with organizational and social innovation. Though attention has focused on direct job creation by major corporations in the IT and business outsourcing industries, huge numbers of job opportunities are also being created for individuals in fields such as research, marketing, publishing, translation, education, business and other types of consulting, vocational training, website development and management, e-conferencing, e-commerce and other fields. Largely unknown to the public-at-large, the potential for Internet-based self-employment remains vastly underutilized. Research is needed to document the full range of Internet-based self-employment opportunities with the potential for large scale job creation and formulate strategies for effective exploitation of this potential.

8.6 Job Guarantee Programs

Constitutionally affirming and legally supporting the right to work provides the very strongest foundation and political will for achieving full employment. This does not mean that government should become the sole or principal job provider as in former communist countries. Rather it means that government should accept the full responsibility and exercise all of the policy instruments available to it to achieve and maintain this goal. Short term, that may well include temporary reliance on government supported job creation programs, such as the US Civilian Conservation Corp during the 1930s. In 2005 India launched a National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme on similar lines, which presently guarantees 100 days of employment per year to more than 45 million families. Unemployment results in high social costs that are normally overlooked, including losses resulting from school dropouts, health and psychological problems, poverty, crime, social unrest and even terrorism. Studies indicate that government-sponsored employment guarantee programs of this type can be a cost-effective option for at least temporarily filling job shortages.55,55,57

8.7 Global Minimum Wage

As Harlan Cleveland so rightly perceived, the real driving force for wealth creation in the 20th century was the rising expectations of ordinary people everywhere. Continuous economic growth requires a continuous increase in effective demand for goods and services, which can only be achieved by raising incomes of the aspiring masses at the lower levels of global society. China and India have been recognized as the world’s future economic powerhouses because they have hundreds of millions of people eagerly desirous of a better life and willing to learn and work to achieve that objective. Henry Ford doubled the wages of his factory labor, so they could afford to buy his cars. Raising the minimum wage in every country to the level required to comfortably meet all human needs will create the most powerful economic stimulus imaginable. Higher wages at lower levels will stimulate untold economic expansion. As Randall Wray has argued, even if sovereign governments simply create more money to raise the incomes of the lowest levels of society, the economic multiplier effect will more than compensate for the costs.28 Global recognition of the right to employment combined with a coordinated global effort to systematically raise incomes at the lower levels of the society will provide the policy base for accelerated growth of incomes and employment the world needs to meet the economic needs, security and welfare of all human beings.

The World Academy’s Global Employment Challenge identified a number of other strategies that illustrate the very broad range of options available for accelerating short, medium and long term job growth by stimulating the underlying process of social development that constitutes the foundation for economic progress and human welfare.30 A combination of these and other strategies can be applied to dramatically reduce unemployment in both developed and developing countries.

8.8 Proposal for Pilot Projects

This paper has explored a range of theoretical and practical issues related to meeting the global employment challenge. It calls for the development of a wider conceptual framework that views employment as one dimension and component of the broader development of society as a whole. The central argument is that the potential for employment generation is unlimited because it is based on the unlimited potential of individual human beings and groups to develop new ideas, values, knowledge, skills, capacities and organizations for self-augmenting social development. The value of theory is best demonstrated by practical application. Therefore, the World Academy and the Club of Rome are jointly exploring the possibility of conducting a pilot project in one country or region of a country designed to dramatically accelerate employment generation through a fresh approach.

9. Evolving a Global Perspective of Employment

The remarkable performance of the global economy in generating new jobs over the past half century has been largely overlooked because employment is viewed primarily from the perspective of individual nations, rather than from the perspective of the world as a whole. It is easy to spot the loss of jobs resulting from outsourcing of production to foreign countries or adoption of mechanized production processes. But the overall effect of social change on the global economy is far more complex and difficult to measure. Jobs that move overseas today help spur income growth in other countries that results in higher consumption, greater demand for imports and greater job growth in other countries sometime later.

These facts do not mitigate the real negative impact of short term job losses, especially those that have come on very rapidly as the result of the international financial crisis. Individuals and some countries may be impacted quite severely by macro level global trends in the short term. Short term problems justify aggressive and innovative measures to cope with a localized problem, but they do not necessarily imply an insoluble problem, either for any individual nation or the world-at-large. The medium term prognosis is quite favorable for creating full employment at the global level.

To understand and fully respond to the challenges of rapid social transformation, we need to develop a comprehensive social theory of employment as well as global models which reflect the complex interacting forces that are reshaping world society in ways that differ substantially from earlier periods in history.

Authors contact information:

Garry Jacobs – email: garryjacobs@gmail.com, website: www.mssresearch.org

Ivo Slaus – email: slaus@irb.hr

Notes:

*Paper presented by Garry Jacobs and Ivo Slaus at the International Conference on Concerted Strategies for International Development in the 21st Century organized by the Club of Rome in Bern, Switzerland, on November 17-18, 2010. The paper was also published in the second issue of CADMUS journal.

1.Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776), 94.

2.Employment in Europe 1995. 1995. European Commission. Available at http://europa.eu/