The Global Job Machine: Trends & Prospects

By Garry Jacobs *

Radical technological advancement and the emergence of a New Economy combined with rapid globalization pose serious challenges to companies, workers, governments and existing ways of work around the world. These challenges demand our serious attention. New perspectives, creative thinking, fresh approaches and innovative initiatives are urgently required. Added to these, we are now suffering the consequences of a global financial crisis which has sent shock waves through the world economy, displacing millions of workers and raising anxieties about a dismal future for young job aspirants. Coupled with the related fears generated by rapid mechanization, ever-expanding population, outsourcing and globalization, the actual or perceived threats to individuals, localities and countries have led some to think that we must urgently prepare ourselves for a future world with too little work.

Do these challenges inevitably point to a dire global shortage of jobs in future? Are we indeed fighting a perpetual uphill and inevitably losing battle against ruthless and relentless impersonal economic forces indifferent to human well-being? Does the global employment situation warrant such pessimism? Do the facts of recent history support the view that we are falling ever farther behind in our efforts to generate work for the world’s growing population. Apart from the temporary effects of the recent recession, is there reason to believe that our children and grandchildren may be heir to a world without work?

Do these questions about a distant future really even matter when the short-term prognosis is so worrying? Our view of the future does matter. It matters very much. If truly the near term prognosis for work is so bleak and hopeless, we may need to radically re-engineer our whole approach to work, livelihoods and consumption or face violent social upheavals by the growing numbers of economically disenfranchised unemployed. But if, instead, factual evidence indicates a rapid expansion of employment opportunities in the future – leading perhaps even to a global shortage of workers – then our response to the current deficit may be very different. It may not mitigate the real suffering brought about by the immediate challenge. But it would certainly make it easier for us to approach the current situation as a temporary aberration with far more confidence, energy, and determined political will.

The Historical Record 1950 – 2007

Compelling misconceptions clouded thinking about employment through much of the 20th Century and continue to hamper rational discussion today. Rapid industrialization fueled fears that machines will soon replace human beings as the principle producers of goods and services in the world. These fears were aggravated by the population explosion that began after World War II, which flooded the global labor market with hundreds of millions of new job seekers. Computerization, outsourcing, globalization and now a major recession have further added to the gloomy picture.

What does the historical evidence tell us about the world’s past performance and future prospects? Contrary to appearances, it tells a remarkable story that belies our fears and compels us to reexamine our underlying assumptions. It depicts the workings of a global economy – a veritable global job machine – that has been creating new jobs even faster than the world’s population has expanded or technological advances have replaced human labor with machines. Over the past sixty years it has generated more than two billion jobs, nearly three as many jobs as the world economy generated during the previous five centuries! It also provides compelling evidence that we need to move beyond traditional national models of employment and evolve a truly global understanding of the factors, forces and processes that govern the world of work.

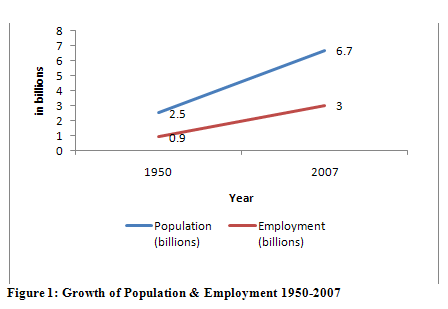

Figure 1 shows growth in global population and employment since 1950. It shows that global job creation has been taking place at record rates for the past six decades. Between 1950 and 2007, global population increased by 168% from 2.5 billion to 6.7 billion.[1] During the same period, total global employment rose 237% from 900 million to 3.1 billion.[2]

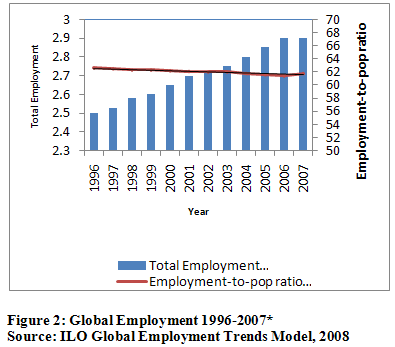

This broad historical trend maintained its positive momentum right up to the onset of the current recession. From 1996 to 2007, global population increased by 16%, while total global employment grew 17%.[3] The world added approximately 400 million more people, yet the global employment to population ratio remained virtually constant as shown in Figure 2. If past trends continue, the global economy will create another 1.3 billion jobs during the next 35 years.[4]

In addition to unprecedented job growth, the last half century has also been a period in which the quality of jobs available worldwide has increased dramatically due to the progressive shift from manual work to mental work. This qualitative improvement in work is indicated by the falling percentage of the world’s work-force engaged in agriculture, one of the lowest paying manual job categories. Globally, employment in agriculture declined from 65% in 1950 to 36% in 2007.[5]

Employment in the OECD

A closer look at what occurred in the USA and other OECD countries is consistent with the global figures. During the 20th century America vigorously exposed its labor markets to the dual threats of technological development and open markets. Recent anxiety regarding the future of employment is similar to that which the US passed through in the 1890s when agricultural mechanization displaced millions of farm workers, generating double digit unemployment and visions of a dismal future. Yet, over the last 100 years, employment in the United States has grown by nearly 100 million jobs or 400%. Between 1990 and 2007, the US economy created 25 million additional jobs.

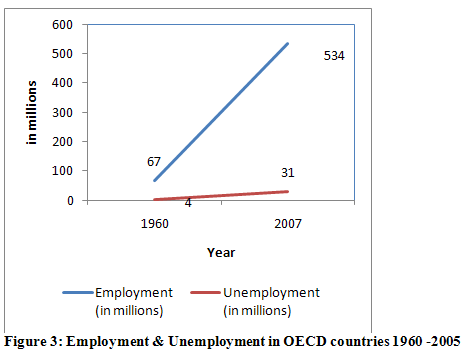

The OECD as a whole as performed in a similar manner. Figure 3 shows that between 1960 and 2007, total employment in OECD countries rose seven-fold, by 467 million jobs, a 78% increase in the proportion of the population employed, including a 49% increase in the participation of women in the workforce[6]. This trend continued right up to the start of the current recession.

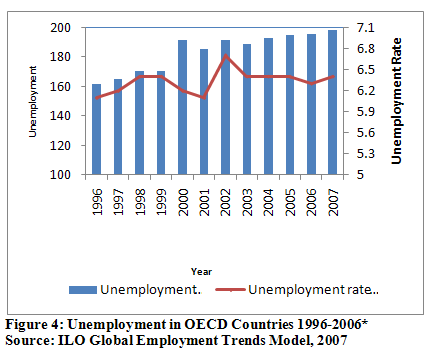

Rising unemployment in the OECD appears to contradict this trend, but it is only an appearance resulting from growth in total population. More people have been working than ever before but in absolute numbers, more people are unemployed; because the population is larger and a higher proportion of the population seeks jobs. Between 1965 and 2007, unemployment in OECD countries rose by only 27 million persons, equivalent to only 6.5% of total job growth.[7] Over the past decade the ratio of employment to population actually rose slightly, while unemployment fell from an average of 7.8% to 6.4%.[8] Figure 4 shows that despite short term fluctuations, the unemployment rate remained remarkably stable at around 6%.

Future Trends: Engines of Job Growth

Two significant trends will strongly influence global employment prospects in the coming decades – rapid economic growth in the developing world and demographic trends in OECD countries. The traditional nation-based perspective of employment fails to take into account the enormous positive impact of global economic growth on job creation, because many of those jobs are created in other countries. Jobless growth is a misnomer. The most economically advanced countries are actually running a net negative unemployment, which is not immediately apparent because we focus only on jobs created in the domestic economy. High income countries are net job exporters.

The impact of job exports is probably highest and easiest to document in the USA. The US currently employs about 12 million workers in its own manufacturing industries, which accounts for about 9% of total employment. In addition it generates work for approximately 21 million additional workers in 12 low cost developing countries, including China, Korea, Mexico, India and other Asian nations. This approximate figure may be taken to represent the net addition to the US workforce after offsetting America’s own manufacturing and service exports to the world. If service imports such as IT and business outsourcing are also taken into account, the total net overseas job creation may be closer to 24 million. This is a rough estimate, but it should be sufficient to illustrate the point that as incomes rise, net job creation occurs both domestically and internationally. If correct, it means that America produces 18% additional jobs overseas and that in normal times it is running a net negative unemployment rate (after deducting domestic unemployment) equal to 12 or 13% of total domestic employment.

This helps explain the remarkable fact that total global employment has more than kept pace with population growth and technological development over the past sixty years. The offsetting factor is higher incomes and greater demand for goods and services, both domestically and internationally. Granted that the net contribution to global employment by most countries is probably much lower than the USA level in both absolute and relative terms, nevertheless the principle should hold universally. As living standards continue to rise in many middle income countries, they too will become net job importers. Even low wage developing countries are becoming job importers. India-China cross-border trade has recently crossed $52 billion. As their economies continue to grow rapidly over the next two decades, these two giant economies, representing 40% of the world’s people, will create hundreds of millions of new jobs, domestically and internationally.

Demographic Trends

The world is now in the early stages of another demographic revolution, which promises to have tremendous impact on the future of employment worldwide. This revolution is the result of a steep and steady decline in the birth rate and an increase in life-expectancy in the more economically-advanced countries.

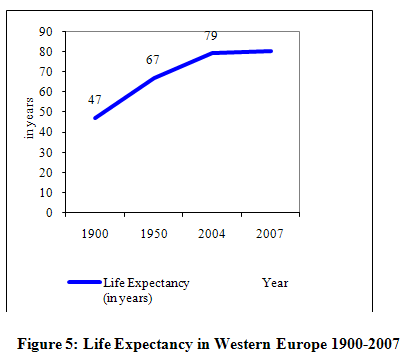

In Western Europe life expectancy has risen from 47 years in 1900 to 80 years in 2007.[9] The result of this trend is a reduction in the number of young people entering the job market and a surge in the size of the elderly retired population. Already 50% of the population in industrialized countries is in the dependent age groups, which includes those under 15 and those over 64.[10] Over the last decade, the old-age dependency ratio – the percentage of people aged 65 and above compared to the number of people aged 15-64 – in these countries has risen from 19% to 22%.[11]

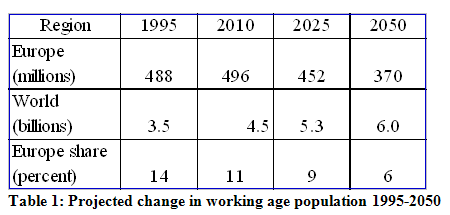

Table I gives the projected growth of the working age population over the next five decades. It shows that the labor force in Europe will level off by 2010 and begin to decline thereafter. Already population growth has become negative in some parts of Europe.

These trends will have enormous impact on the future of employment. The EU’s labor force is expected to shrink by about 0.2% a year between 2000 and 2030.[12] The old age dependency ratio will rise from 22% in 2000 to 35% in 2025 and 45% or 50% in 2050.[13] As the old age population grows, the working age population will shrink. The EU25 is expected to lose an average of one million workers a year.

A UN study released in March 2000 estimates that the EU-15 would have to accept 170 million new immigrants over the next 25 years in order to maintain present levels of working and tax-paying population.[14] A World Bank Study estimates that 68 million immigrants will be needed to meet labor requirements during the period from 2003-2050.[15] These estimates have been challenged, but there is little doubt that unless major policy initiatives are taken; the net result will be a dramatic decline in the relative size of the working age population in Europe and a shortage of workers to fill the available jobs.[16] Recognition of this fact is already prompting major policy shifts within the EU, which has adopted a goal of raising labor force participation rates to 70%, while the average for the EU-15 was only 65 years in 2005. It has also spurred efforts to increase participation of women in the workforce.

Similar trends will prevail in other countries. The same UN study estimated that Japan would need to admit 647,000 immigrants annually for the next 50 years in order to maintain the size of its working population at the 2000 level.[17] By 2013, labor-force growth in the United States will be zero. The US is forecast to have a shortage of 17 million working age people by 2020. China will be short 10 million.

India is expected to have a surplus of 47 million in 2020,[18] but there is evidence that even in India, the surpluses may prove illusory. Reliable data on employment growth in India is confined to the formal sector which represents less than 10% of total jobs. Empirical evidence suggests actual job growth is far higher than official measures. Otherwise with seven million new job seekers entering the labor market each year, unemployment would have swelled enormously in recent years; whereas in fact both urban and rural employers report increasing difficulty attracting the workers they need. As indirect evidence of a tightening labor market in India, salary levels in the formal sector are rising at 14% annually and are projected to be the fastest rising in Asia. Wages in unskilled work in some non-metropolitan and rural parts of the country are rising even more rapidly.

The projected job shortages in developing countries are based primarily on anticipated domestic economic growth and demographic trends. They do not fully take into account the growing demand for jobs created by rising economic prosperity in other countries.

Need for a Social Theory of Employment

Objective facts are not sufficient. We need also clarity of thought. Misconceptions have surrounded notions of employment for so long that they are likely to persist, even in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, unless fact is supported by rational analysis. The circumstances that are now creating a favorable social environment for full employment are not merely an accident. They are driven by fundamental social forces.

A day may soon come when we look back on periods of high unemployment as a short term anomaly of adjustment that occurred during the transition from agrarian-industrial to post-industrial society. The past two centuries broke a pattern of economy that had been dominant for nearly 10,000 years. The dawn of the Industrial Revolution ushered in a period of radical transition. England was the first to make that transition. Employment in agriculture fell to 11% of total employment by 1900, at a time when agriculture still represented 40% of total employment in France, Germany and USA, and probably as much as 75% globally. Between 1870 and 1970, agricultural employment in the USA declined from 50% to 4% of the workforce, yet all these workers and twice as many additional workers were absorbed in other types of work. How were all these disenfranchised agricultural workers re-employed so quickly?

To the upheaval of economic transition was added the immense impact of two world wars, innumerable civil wars, unprecedented immigration, and the advent of modern antibiotics and medical care, which were responsible for a phenomenal 2.6-fold growth of world population after 1950. A similar process is now going on in developing countries, where the percentage of the workforce engages in agriculture is falling rapidly and new technology is being adopted at record speed. In spite of all these factors, we still find that growth of employment has actually outpaced population growth during this period. The question is ‘how?’

We cannot answer this question by viewing economy and employment in abstraction – as if they were determined by fixed, universal laws like the Laws of Thermodynamics – or in isolation – as if they functioned separately independently from society as a whole. A satisfactory answer can only be found by examining economy and employment as human processes which are governed by political, social and psychological forces determined by a wider and ever-evolving social context.

When we do this, the first thing we note is that employment is a function of human aspirations and those aspirations have been rising dramatically over the past two centuries, particularly after 1950. Human initiative depends on what people perceive as possible and desirable. For many centuries, the confining structure of feudal, autocratic, class-bound societies placed severe limits on those aspirations. A combination of political democracy, social liberalism, technological development and universal education have broken down the barriers to individual and social progress, resulting in a revolution of rising expectations which began in North America and Europe and has since circled the globe to awaken the aspirations of people everywhere. Higher aspirations generate greater energy, productivity, experimentation, innovation and pioneering initiatives. People want more and demand more, creating job opportunities for other people to fill. Rising aspirations have been the principal driving force behind unceasing productivity growth.

Nor is there any indication that this process is nearing a limit, even in the most economically advanced nations. In those countries, the desperate need for food and clothing has been replaced by an unquenchable quest for travel, better health care, higher levels of education, more information, recreation and entertainment. It is now possible for 2% of the population to produce all the food a nation requires, but it requires 80% or more to meet its rising demand for services. Demand for food is finite and subject to severe limits. Demand for services is virtually unlimited.

During the 20th century we witnessed many instances in which the advent of a new technology or foreign imports eliminated jobs. What we did not notice was the overall impact of rising levels of technological sophistication on the need for new types and larger numbers of workers in education, research, product development, sales and service or the corresponding growth of jobs in sectors that catered to growing foreign markets.

It is now becoming apparent that every advance in social development has this dual effect – eliminating jobs in older sectors and creating jobs in new fields. New jobs are created as a result of the development of new services (Internet), growth in consumer demand (mobile phones), higher productivity resulting in lower cost (personal computers), a growing spirit of entrepreneurship (internet start-ups), greater access to information (on-line job exchanges and marketplaces), technological innovation (iPod and iPhone), organizational innovation (micro-lending), higher quality standards (education), legislation and enforcement (food quality, energy conservation), greater administrative efficiency, greater health consciousness and environment awareness, higher skills (engineering), increased speed (air travel), change of attitudes (working women), etc. This unlimited capacity of society to generate new jobs was noted by the International Commission on Peace and Food in its report:

The notion that there are a fixed or inherently limited number of jobs that can be created by the economy is a fiction. It is not just advances in technology that work in this fashion. Every major advance in social attitudes, institutions, values and lifestyles has a dual effect on employment, creating jobs in some areas and destroying them in others. Higher standards of education not only raise productivity, but also stimulate higher expectations that lead to greater consumption. Changing attitudes toward the environment have created entirely new industries and generated new jobs in every field where impact on the environment is of concern. New types of organization such as fast-food restaurants, franchising and hire purchase or leasing create new jobs by hastening the growth or expanding the activities of the society. Shifting attitudes toward marriage and the role of women create greater demand for jobs but also more opportunities for employment, because working women consume more and require additional services.[19]

From the individual’s point of view, the relationship between human aspirations and employment generation is direct and self-evident. Every person who comes into the world brings with him a basic set of physical and non-material needs which have to be met largely by other people during a long period of childhood and an increasingly long period of old-age. We have already seen that that set of needs is increasing rapidly and not subject to any inherent limits. Assuming the average person works for 200 days a year during 50% of his lifespan, it is equivalent to working for less than 30% of total days he is alive. Consider also that our requirement for goods and services spans at least 16 hours a day and in some cases 24 hours, which is two to three times greater than the actual time we spend in working, meaning that we work only about 10-15% of the actual time we consume. Furthermore, those who work to provide us with our needs also work only 10-15% of the time they live, which means that if each of us required the full-time assistance of one person to provide for our needs round-the-clock, we would require 40 to 100 times as many work-providers as we have consumers, since each of them works only 10-15% of their own lifetime as well.

Obviously this cannot happen and does not happen. Rising levels of productivity resulting from technology, social organization, education and training make it possible for each human being to produce far more than is required for personal consumption. There is no inherent limit to this rising productivity. But there is also no inherent limit to the range and quantity of needs to be met. And at the higher end of the spectrum, needs such as education and medical care tend to require higher levels of labor input.

Evolving a Global Perspective of Employment

The remarkable performance of the global economy in generating new jobs over the past half century has been largely overlooked because employment is viewed primarily from the perspective of individual nations, rather than from the perspective of the world as a whole. It is easy to spot the loss of jobs resulting from outsourcing of production to foreign countries or adoption of mechanized production processes. But the overall effect of social change on the global economy is far more complex and difficult to measure. Jobs that move overseas today help spur income growth in other countries that results in higher consumption, greater demand for imports and greater job growth in other countries sometime later.

These facts do not mitigate the real negative impact of short term job losses, especially those that have come on very rapidly as the result of the international financial crisis. Individuals and some countries may be impacted quite severely by macro level global trends in the short term. Short term problems justify aggressive and innovative measures to cope with a localized problem, but they do not necessarily imply an unsolvable problem either for any individual nation or the world-at-large in the medium or long term. The medium term prognosis appears quite favorable for creating full employment at the global level.

To understand and fully respond to the challenges of rapid social transformation, we need to develop a comprehensive social theory of employment as well as global models which reflect the complex interacting forces that are reshaping world society in ways that differ substantially from earlier periods in history.

________________________

*Author is Vice-President of The Mother’s Service Society, Pondicherry, India

[1]. U.S. Census Bureau. (2008) U.S. and World Population Clocks – POPClocks [Internet]. Available from: <http://www.census.gov/main/www/popclock.html> [Accessed 20 August 2008].

[2] Ghose Ajit, Majid Nomaan and Ernst Christoph. (2008) The Global Employment challenge [Internet], International Labour Organization. pp.1, Available here [Accessed 12 August 2008].

[3] International Monetary Fund. (2006) World Economic and Financial Surveys [Internet]. Available here. [Accessed 21 August 2008].

[4] International Commission on Peace & Food. (1994) Uncommon Opportunities: Agenda for Peace and Equitable Development, [Internet], Zed Books, Chapter 4. Available from: <http://icpd.org/UncommonOpp/CHAP04.htm> [Accessed 15 August 2008].

[5] International Labor Organization. (2008) Global Employment Trends [Internet]. Available from: <http://www.ilo.org/public/english/employment/strat/download/get08.pdf> [Accessed 20 August 2008].

[6]International Labor Organization. (2008) Global Employment Trends for Women 2008 [Internet], Press Release, 6 March. Available here [Accessed 20 August 2008]

[7]OECD Stat Extracts. Dataset: LFS by sex and age [Internet]. Available here. [Accessed 14 August 2008].

[8] International Labor Organization. (2008) Global Employment Trends [Internet]. Available from: <http://www.ilo.org/public/english/employment/strat/download/get08.pdf> [Accessed 20 August 2008]. pp.11.

[9] Giarini, Orio and Liedtke, Patrick M. (1996) The Employment Dilemma and the Future of Work, Report to the Club of Rome, pp.64 and United Nations. (2006) World Populations Prospects: The 2006 Revision [Internet]. Available here.[Accessed 21 August 2008]. pp.80

[10] Giarini, Orio and Liedtke, Patrick M. (2006) Abstracts from The Employment Dilemma and the Future of Work [Internet]. European Papers On The New Welfare. Available from: <http://eng.newwelfare.org/?p=47&page=7> [Accessed 21 August 2008]. pp.7.

[11] Giarini, Orio and Liedtke, Patrick M. (1998) The Employment Dilemma and the Future of Work, Report to the Club of Rome, pp.61.

[12] Eberstadt, Nicholas and Groth, Hans. (2007) Healthy old Europe [Internet]. International Herald Tribune, April 20. Available from: < http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/04/19/opinion/edeber.php> [Accessed 18 August 2008].

[13] Munz, Rainer. (2004) Migration, Labor Markets and Migrants’ Integration in Europe: A Comparison [Internet]. Migration Research Group. June 28-29. Available here. [Accessed 13 August 2008]. pp.19.

[14] Fotakis, Constantinos. (2000) Demographic Ageing, Employment Growth and Pensions Sustainability in the EU: The Option of Migration [Internet]. Expert Group Meeting on Policy Responses to Population Ageing and Population Decline, United Nations Secretariat. October 16-18. Available here. [Accessed 12 August]. pp.6.

[15] Raihan, Ananya. (2004) Temporary movement of Natural Persons: Making Liberalisation in Services Trade Work for Poor [Internet]. Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics-Europe, May 10-11. Available here. [Accessed 20 August 2008]. pp.20.

[16] Slaus, Ivo. (2004) European Institute of Technology – An attempt of Euclidean Justification, South East European Division of the World Academy of Art and Science.

[17] United Nations Population Division, Replacement Migration. Population Indicators for Japan by Period for Each Scenario [Internet]. Available here. [Accessed 14 August 2008].

[18] Ramachandran, Sudha. (2006) Doubts over India’s ‘teeming millions’ advantage [Internet]. Asia Times, May 5. Available from: <http://www.atimes.com/atimes/South_Asia/HE05Df01.html> [Accessed 25 August 2008].

[19] International Commission on Peace & Food (1994) Uncommon Opportunities: Agenda for Peace and Equitable Development [Internet]. Zed Books, pp.73. Available from: <http://icpd.org/UncommonOpp/CHAP04.htm> [Accessed 15 August 2008]